REVIEW: Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

PHOTOS | KEL McINTOSH

If you picked up this book recently, it's probably because you’ve heard it's a classic, you love motorcycles, and you feel guilty as fuck that Robert M Pirsig died before you actually got around to reading it*. Or is that just me?

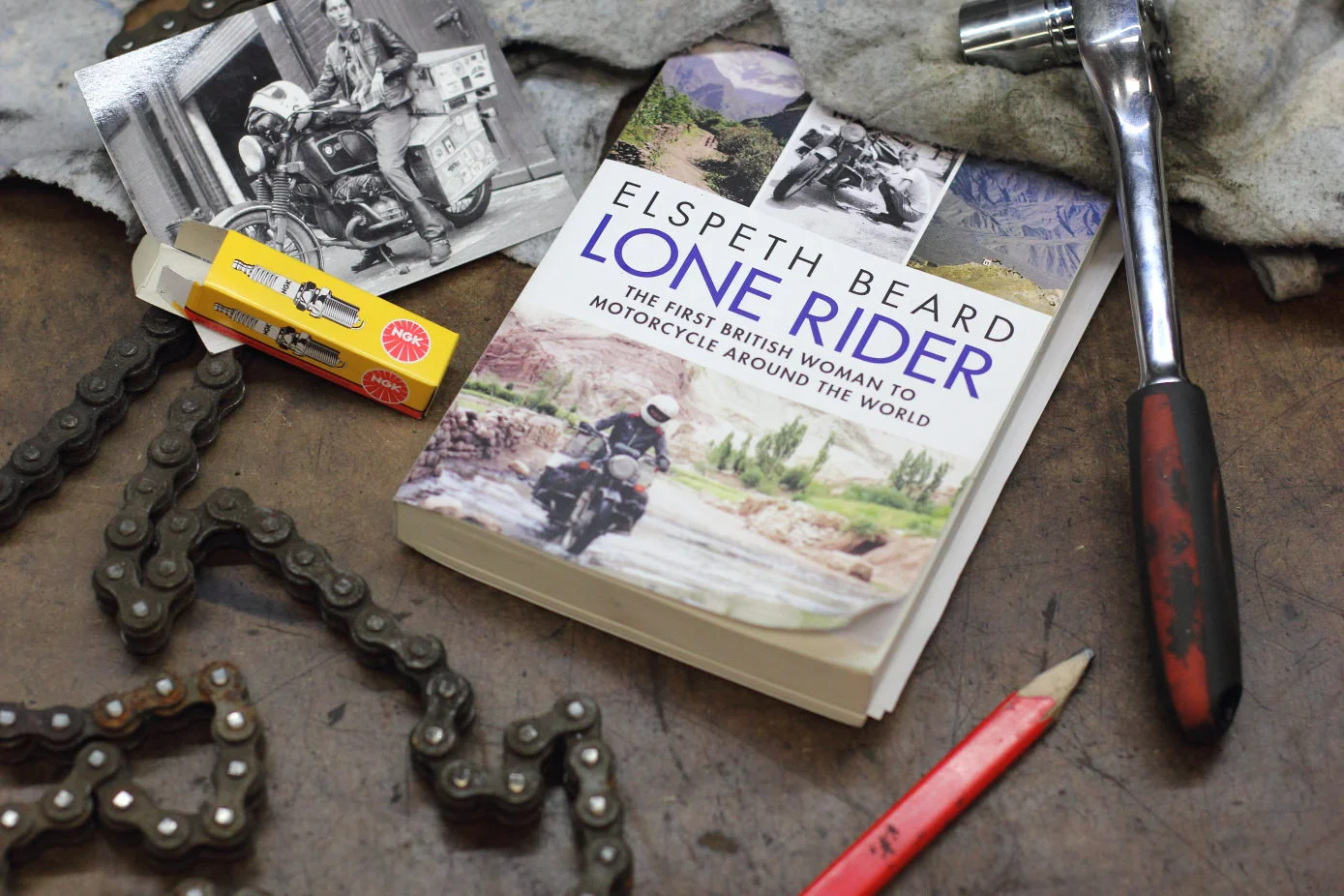

Image Source: Robert Hood Wheels

Pirsig’s fictionalised autobiography recounts the journey of the author and his son, Chris, venturing across the north-west of the United States, sallying forth from Minneapolis in Minnesota, onto North Dakota, crossing Montana (overlapping part of my own recent journey), Idaho, Oregon and culminating in Northern California. There are two plot lines explored: that of the author and his son’s relationship while riding interstate, and that of Phaedrus and his ‘chautauquas’ and boundless (and at times relentless) quest to define Quality.

The tale delves a bit more into metaphysics than motorcycle maintenance but the connection is irrefutable, and provides food for thought on the many processes required to function concurrently and harmoniously to propel you forward, be it on machine or otherwise.

Often stubborn to a fault, Pirsig’s stoicism in the face of his son’s desire to connect with him can be frustrating. On the other hand, Phaedrus’ ‘knife’ (which is so eager to divide things into ever smaller parts for analysis) can feel callous to those who recognise value in grey areas; even the narrator finds fault in approaching everything solely from this method. Still, there are merits for mortals to be found in the harsh divisions. I found myself reading and re-reading Pirsig’s analysis of ‘Gumption’ (the character trait, not the cleaning paste), with an anxiety activity in chapter 26 that is applicable to both bikes and life. Even if you only read chapter 26, you might find yourself a little more zen.

“Anxiety, the next gumption trap, is sort of the opposite of ego. You’re so sure you’ll do everything wrong you’re afraid to do anything at all. Often this, rather than “laziness,” is the real reason you find it hard to get started. This gumption trap of anxiety, which results from over-motivation, can lead to all kinds of errors of excessive fussiness. You fix things that don’t need fixing, and chase after imaginary ailments. You jump to wild conclusions and build all kinds of errors into the machine because of your own nervousness. These errors, when made, tend to confirm your original underestimation of yourself. This leads to more errors, which lead to more underestimation, in a self-stoking cycle. The best way to break this cycle, I think, is to work out your anxieties on paper. Read every book and magazine you can on the subject. Your anxiety makes this easy and the more you read the more you calm down. You should remember that it’s peace of mind you’re after and not just a fixed machine.”

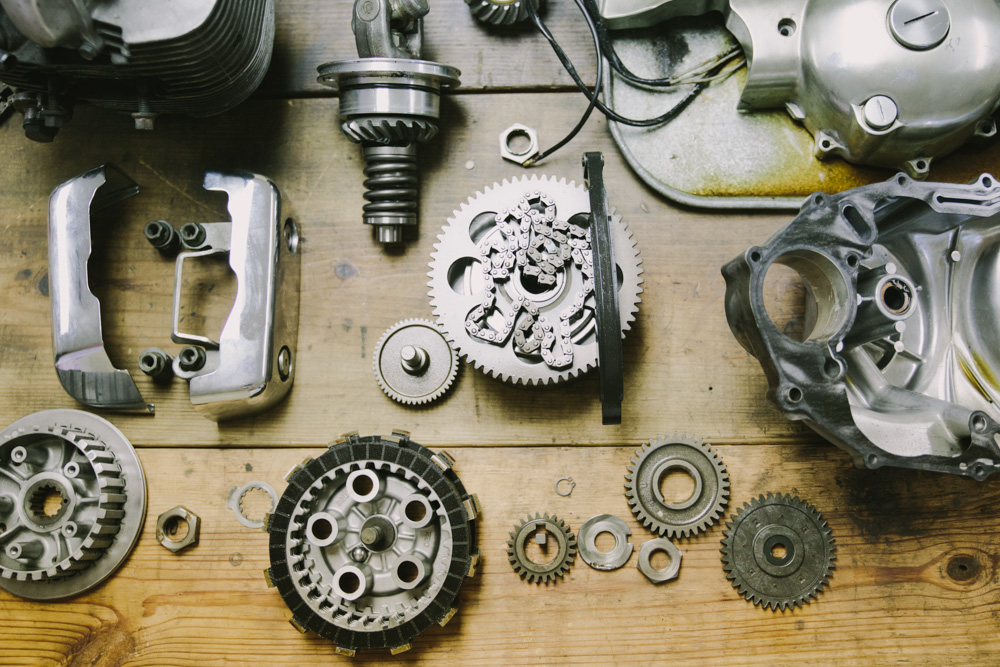

Image Source: Flickr

If you are struggling with the philosophy aspect of the book, you could probably read it by skipping paragraphs (but that is kind of cheating). Not being a philosophy major myself, I found the Phaedrus and Quality rants got a little long in the tooth, however I implore that you persist - there is purpose. I still don’t understand it all, but then again, there are many things I don’t understand. But I am at no risk of being any less a person for making the effort to understand. This one certainly deserves a re-read.

*This, unfortunately, is also the exact way I discovered Christopher Hitchens.

Reviewer's note: Personally, I am a stickler for purchasing hardcover first edition books. Call it habit, call it obsession, whatever. I’ve always felt at home in a library and, naturally, having a library at home is on par with having my own shed. My copy of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance is the 1974 copy so when I was up to page 324 and had to head out of town, my first edition hardcover didn’t quite make the light-packing cut. While traveling I became so desperate to finish the book I downloaded a pdf copy of the 1984 version which contained an afterword (not in the first ed obvs), the reading of which had me in tears. If I had only read the earlier edition, I’d never have known of the afterword’s existence, and that knowledge has now adjusted my perspective on the value of editions beyond the usual notion that the “publisher wants to shuffle out another reprint”.

Editor's note: Zen tends to elicit descriptions of favourite quotes. Mine are:

“Precision instruments are designed to achieve an idea, dimensional precision, whose perfection is impossible. There is no perfectly shaped part of the motorcycle and never will be, but when you come as close as these instruments take you, remarkable things happen, and you go flying across the countryside under a power that would be called magic if it was not so completely rational in every way.”

“Such personal transcendence of conflicts with technology doesn’t have to involve motorcycles, of course. If can be at a level as simple as sharpening a knife or sewing a dress or mending a broken chair. The underlying problems are the same. In each case there’s a beautiful way of doing it and an ugly way of doing it, and in arriving at the high-quality, beautiful way of doing it, both an ability to see what ‘looks good’ and an ability to understand the underlying methods to arrive at that ‘good’ are needed. Both classic and romantic understandings of Quality must be combined.

The nature of our culture is such that if you were to look for instruction in how to do any of these jobs, the instruction would always only give one understanding of Quality, the classic. It would tell you how to hold the blade when sharpening the knife, or how to use a sewing machine, or how to mix and apply glue with the presumption that once these underlying methods were applied, ‘good’ would automatically follow. The ability to see what ‘looks good’ would be ignored.

The result is rather typical of modern technology, an overall dullness of appearance so depressing it must be overlaid with a veneer of ‘style’ to make it acceptable. And that, to anyone who is sensitive to romantic Quality, just makes it all the worse. Now it’s not just depressingly dull, it’s also phony. Put the two together and you get a pretty accurate basic description of modern American technology; stylized cars and stylized outboard motors and stylized typewriters and stylized clothes. Stylized refrigerators filled with stylized food in stylized kitchens in stylized houses. Plastic stylized toys for stylized children, who at Christmas and birthdays are in style with their stylish parents. You have to be awfully stylish yourself not to get sick of it once in a while. It’s the style that gets you; technological ugliness syruped over with romantic phoniness in an effort to produce beauty and profit by people who, though stylish, don’t know where to start because no-one has ever told them there’s such a thing as Quality in this world and it’s real, not style. Quality isn’t something you lay on top of subjects and objects like tinsel on a Christmas tree. Real Quality must be the source of the subjects and objects, the cone from which the tree must start.”

Kel has the face of a siren and the mouth of a drunken sailor. When not whispering sweet nothings to her CM250c, ‘Bronson’, she can be found in a museum, library or a bar.